From firing range to fired by the BBC.

Paul 'The Assassin" Baird recounts the time he was fired by the BBC and found himself interviewed by a legend of Scottish broadcasting.

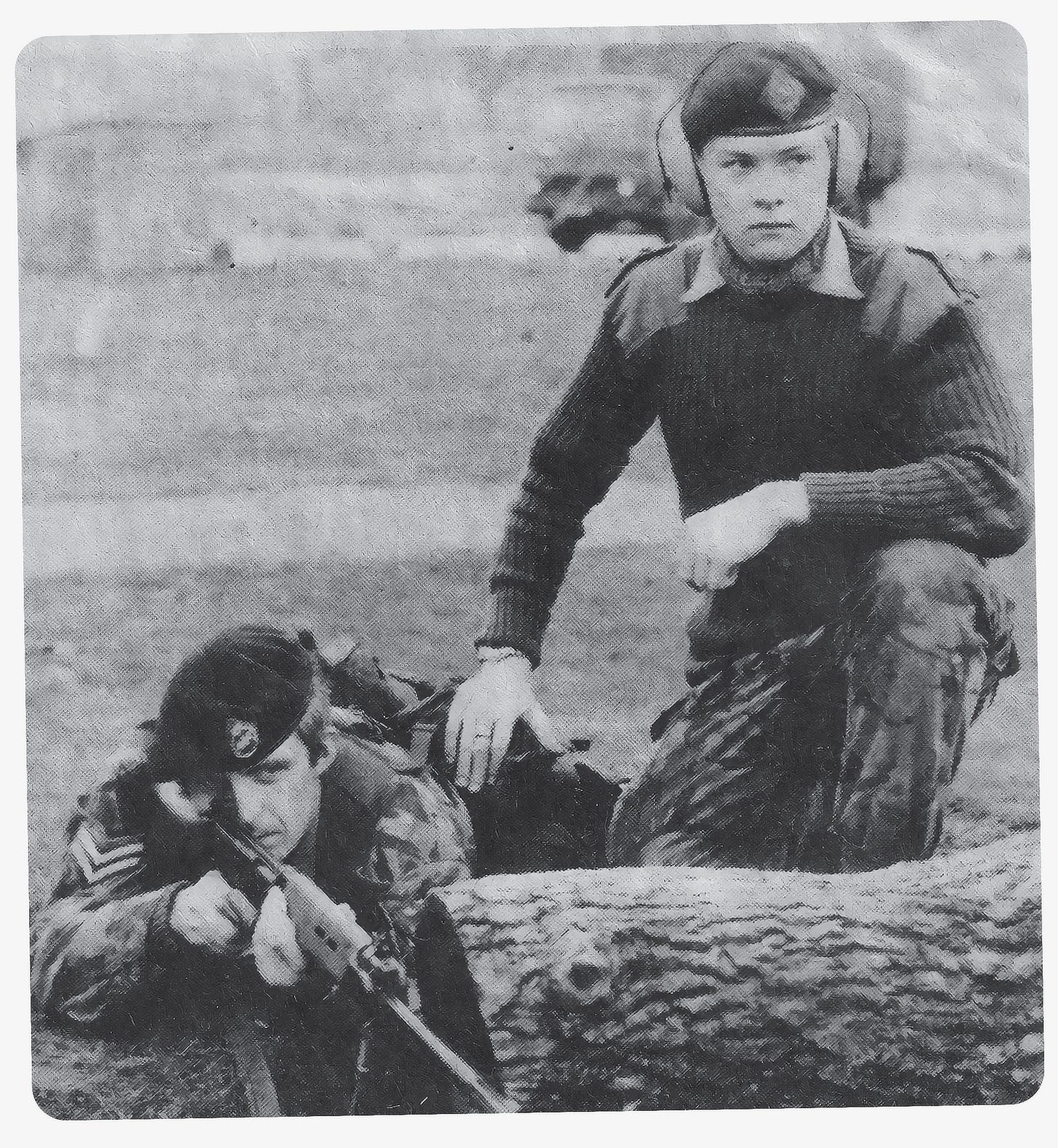

It was the early 1970s and I was kneeling behind a log on an army firing range trying to make sure my soldiers and I didn’t get accidentally shot as they happily expended the army’s ammunition. My service as a reserve officer was proving to be a lifesaver, supplementing a meagre wage as a part-time assistant in local radio. I didn’t broadcast this fact at the BBC as some colleagues would’ve been horrified.

A short tap on the shoulder and a breathless “the Colonel wants to see you now sir” came from one of my lads. It didn’t sound like it would end well as the Colonel rarely spoke to lowly lieutenants.

“Ah Baird, just had a call from a bod purporting to be your manager from the BBC saying you’ve just been fired, and he thought you would like to know straight away. Probably best if you pop off to sort it out, eh?” “Yes Sir, thank you Sir.”

So that was it. My tenuous hold on a BBC contract was over. I wasn’t surprised. I’d not even been paid for my first year and only kept my position by staying in the shadows and learning the ropes by being invisible. The future looked bleak. With only a handful of GCSE’s–only degrees from Oxford or Cambridge mattered–I had more chance of being taken on as a consultant surgeon at Guys hospital than getting a staff job at the British Broadcasting Corporation.

I’d passed my exam for the British Police and the Hong Kong police too, (inspector rank, shorts and a revolver included.) Although tempted, an advert for a station assistant in Inverness was shoved in my hand by a newsroom reporter who felt sorry for me.

Much to my surprise I was granted an interview and a few weeks later found myself in the highland capital being interviewed by one of the legends of Scottish broadcasting, William Charrocher. This wickedly funny, intelligent former-foreign office mandarin, fluent Gaelic speaker and newly appointed manager of BBC Highland, cast his experienced eye over the exact opposite, me.

'“Army young man?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Regiment?”

“Kings Own Royal Border Regiment, sir.”

“Excellent.”

“Lord Robbins tells me you can operate this strange equipment he’s installing.”

“Yes, sir.”

At this point, I must explain that all Bill’s flock were given nicknames. Lord Robbins was, in fact, the chief engineer and not a Lord at all. Bill’s secretary (who was taking notes) was called bungy (soft g) as he said the glasses she wore looked like two bungalows. These were quite trendy for the early 70s. If you worked for William Charrocher these things made perfect sense.

The equipment I was working with was the mark three radio desk. Scotland had ended up installing these because it hadn’t the first idea of how a small station should be set up, and never had one before. I was the only person who applied that could operate the equipment. I was also an army officer, which in itself was enough for Bill, so I was in! I knew this was a miracle because the deputy head of my English Radio station had said it was a very bad day for broadcasting, and that he’d put in a good word for me if I wanted a job as a welder at the local nuclear processing plant. He should have said that before, I would have considered it!

Oh, and of course, as one of William’s flock I was given a nickname. As a military type I would have considered ‘Braveheart’ or ‘The Assassin’, both could have worked but no, I was “Dobbin” the workhorse of William Charrocher’s happy band of Highland broadcasters.

Bless you Bill, no longer with us but you are remembered fondly and with much gratitude by “Dobbin”, one of your small happy team.

Hopeful Traveller is a weekly newsletter and archive of stories about broadcasting in the 1970s and 80s. It is written by former-newsreader and programme maker Paul Baird. For new stories each week, subscribe.