Let there be light!

Paul find his new job as a presenter and reporter in regional television illuminating.

Puff, Puff “Nope”

“Could we force it a stop?”

Puff, Puff “Nope”

It was an early morning in the depths of winter and I was standing with my cameraman in the middle of a field, freezing and exasperated. In one hand the cameraman clutched his ubiquitous pipe and puffed out clouds of dense acrid smoke. In the other, he held aloft the dreaded light meter.

I had been sent out first thing to grab an interview and pictures with a local farmer regarding an ongoing agricultural crisis. I should then bring it back, and send it to the national news in London for the lunchtime bulletin. The problem was, we were working on film and it was too dark for the camera.

To be fair, the cameraman, while not impressed with his early start was not being difficult. These were the days of film and if the light wasn’t there you didn’t shoot a frame. The farmer thought we were just being difficult as it wasn’t night time but from our point of view it may have well been.

The light was only the beginning of our problems. Our company used a cheaper film stock which already had a reputation of turning things a bit blue and though we shot on fast positive film the results could be a touch grainy. Using negative film, which required further processing, would take too long and would not make the news on time.

When the light got to a certain level you couldn’t work. We could force the film in processing if the cameraman agreed, but the result was far from good and was frowned upon. So, there I was, with the chance to go on national television but I couldn’t do anything until the light levels rose.

Unfortunately, the light didn’t rise sufficiently enough in time and I never made the national lunchtime news.

This was not the only the difficulty for a budding television film reporter. Not only did the light work against you but the crew made you take other critical decisions.

“Tungsten or Daylight?” the crew chief would ask. Hmm, difficult. If you were filming outside you used ‘daylight’, but if inside you’d use Tungsten film stock. Of course, it was never that easy if you wanted to do both. If you decided on Tungsten and then you went outside, forget it, outside shots turned a rather pretty shade of blue, seriously unimpressive and embarrassing.

Then if you were outside and wanted to go inside the electrician (who usually had been asleep in the crew van) was disturbed and asked to light the scene. These were the days of powerful unions. No reporter was allowed out until he had a cameraman, sound recordist and electrician, regardless of whether they were needed or not.

An interview would require the cameraman to set up a lighting rig. Three 500-watt lights called “Red heads” or if the cameraman wanted something a bit more impressive two 1000-watt lights called “Blondes” (the former being painted red, the latter yellow, hence the nicknames). These would be provided by the electrician. Oh, how long did this take! While the crew set the scene with the light you talked gibberish to the guests who were rapidly becoming bored and running out of patience. Then, if you got all that right there was the dreaded “short end.”

Each magazine had 400ft (125 metres) of film. This would last for 11 minutes. If you were really organised and did all your elements in that time then you wouldn’t have to wait for the cameraman to reload another magazine. If you failed, however, then this cameraman (whilst smoking his pipe) would get out a large black bag with two hand-holds and unload and reload the magazine. This took time. Trust me, you learnt not to shoot too much. Cameramen were notoriously mean and without telling you would load a bit of film they had left over from another shoot (perhaps 200 feet, a ‘short end’). This could last only 5 minutes and just when you got to the critical bit of the interview he would shout “Out of film!” NO!!!!!!…………………………..and out came the bag!

The most dangerous challenge often didn’t come from the crew, however, but the creative aspirations of your Head of News.

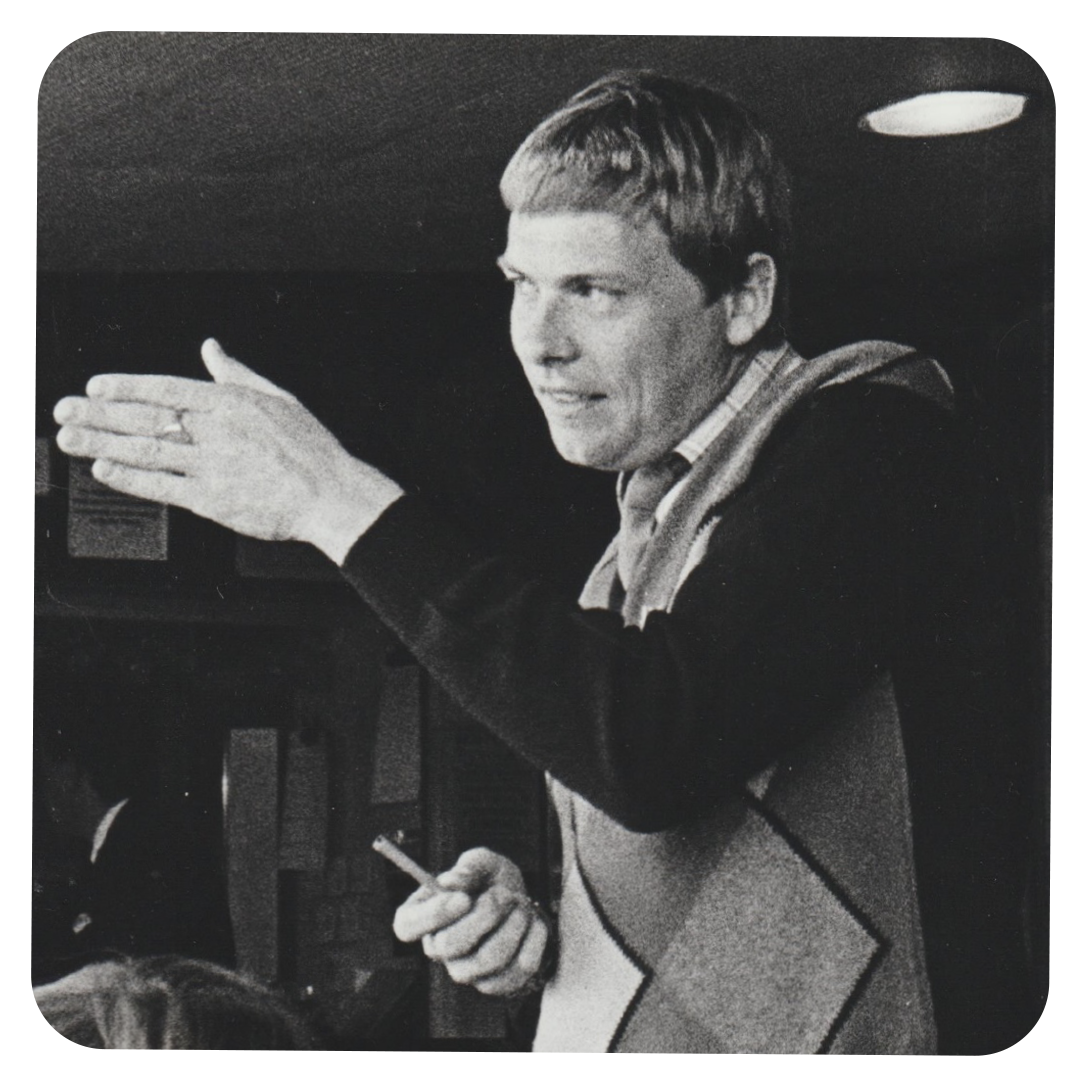

“I’ve just had this amazing lunch and I’ve got an exciting idea; jumpers” said the Head of News. The lunch was with the chief executive of an international woollen manufacturer (based locally) who had offered to kit each reporter/ presenter out with the latest in jumper fashion. These garments were the must-have on the world golfing circuit, very much in demand, and expensive. These were cashmere, had a unique bold diamond pattern and available in some gaudy colours. They were also a global talking point at the time.

We protested. We were serious journalists. But this wasn’t a democracy. So, out went our suits (luckily for our female colleagues they were excluded from this fashion car crash). While it may have been de rigueur for golfers it was quite frankly bizarre for news reporter/presenters. The Head of News was determined, and shortly thereafter me and my colleague Eric sat presenting the news programme in our diamond jumper finery.

Luckily, it didn’t last long before it was quietly dropped. I wasn’t really concerned to be honest, I had my dream job and would have worn a lot worse but my colleague Eric, his jumper was quite frankly too tight and he looked like the harlequin character from the commedia dell’arte. He was a consummate professional, however, and said not a word of complaint. Sadly, Eric is no longer with us but amongst my many happy memories of him are the two of us, doubled over with laughter in the make up room prior to our debut with our nightly television audience.

Hopeful Traveller is a weekly newsletter and archive of stories about broadcasting in the 1970s and 80s. It is written by former-newsreader and programme maker Paul Baird. For new stories each week, subscribe.