The dangers of food in the FSU

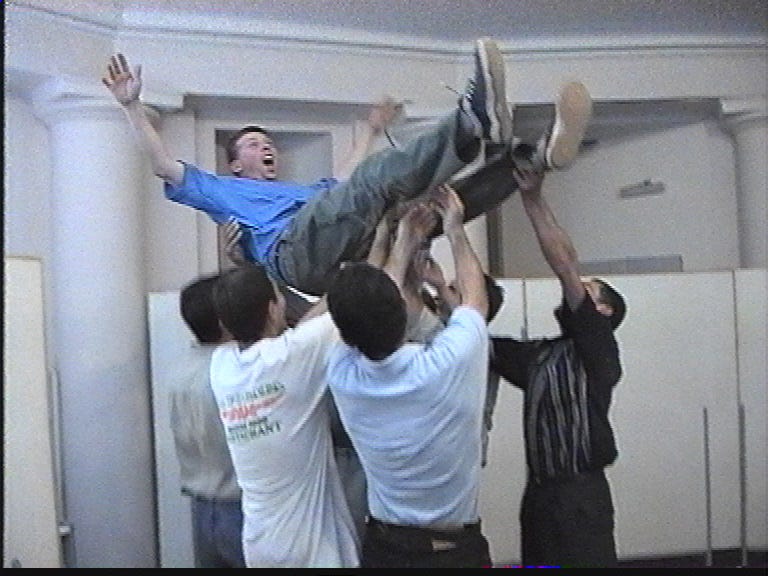

The end of another energetic course in Yerevan, Armenia

To this day I am not sure where I was for this expedition. My notes show that it was the early nineties and I had just finished a filming course in Armenia. For the next assignment, I had flown from the UK to Frankfurt, Germany; then on to Almaty in Kazakhstan and finally to Osh in Kyrgyzstan. From there it was distinctly vague. Hours in a very old bus, mile after mile until, as night fell, we arrived at a former soviet complex that had seen better days.

The accommodation might have been basic but the students were keen for our training and we were always given the very best that could be found in the way of food and accommodation.

Alcohol was, however, another matter. In the very early days, a consultant had to be evacuated having drunk local spirits that were so unfiltered he had developed temporary blindness! So, from then on, at the start of each course, we instructors were issued with coke-sized cans coloured bright blue and containing our vodka ration. Under no circumstances if it was available, were we to drink local alcohol. Now, it probably was a myth, but we believed that it was only through the consuming of vast quantities of these cans that we warded off potential food poisoning.

On this occasion, all our food was to be provided on site as we were far from civilisation. Our cook however, was terrifying. Large and imposing, with only one dish, it seemed in her repertoire, horse. Every day this meat was hacked into submission with an axe, then boiled and served in some form, 3 times a day. As a soup for breakfast, with rice or grains for lunch and dinner. And so, it went on and on. We were told it was a speciality in Kyrgyzstan, called ‘Plov’.

It might well have been ‘Plov’ made by another chef but in the hands of our cook it certainly was not.

To me, and most of my team it was just part of the experience and the vodka took the edge off the taste (even at breakfast). But for our French cameraman Jacque it was all too much. As the days progressed he started to waste away. Looking through sunken eye sockets he said to me “It is alright for you, you are English and brought up to eat sh*t but for me, a Frenchman, it is too much.”

I could have been upset by his comments but I had been raised in Northern England in the fifties and, to be fair, he had a point. So, I suggested to the organiser that, to save our cameraman, Jacque be allowed to cook one meal. That was agreed.

So off to the market went a much cheerier Jacque to buy ingredients and we, the remainder of the team looked forward to being saved from “Plov” for one meal.

That night we all gathered in expectation to see what our Parisian friend would serve up. We had even invented a vodka-based cocktail to celebrate the occasion.

Then, from the kitchen, crash! The sound of pots being thrown and over the serving counter Jacque threw himself into the dining room and kept on going.

In the hatchway, clutching her trusty axe, was our cook. The operation had been planned to the last detail, bar one, nobody had told her Jacque was to take over her kitchen for the evening!

After some negotiation, she was placated, but it was too late. Jacque could not be persuaded to re-enter the kitchen, and the cook was too insulted to prepare dinner.

Still, the cocktails were good, thanks to our trusty supply of blue cans.